Endangered Species Recovery Program | |

|

Home | News | Publications | Species profiles | Data and maps | About | Staff | Links | Department of Biological Sciences | CSU Stanislaus |

Recovery Plan for Upland Species of the San Joaquin Valley, California

Contents

. Introduction

. Species accounts

. Recovery

. Stepdown

. Implementation

. References

. Appendix

4. Riparian Woodrat (Neotoma fuscipes riparia)

- Taxonomy

- Description

- Identification

- Historical Distribution

- Current Distribution

- Food and Foraging

- Behavior and Species Interactions

- Habitat and Community Associations

- Reasons for Decline

- Threats to Survival

- Conservation Efforts

- Conservation Strategy

- Conservation Actions

Taxonomy.-- The riparian or San Joaquin Valley woodrat, Neotoma fuscipes riparia, is one of 11 described subspecies of the dusky-footed woodrat (Hooper 1938). Although some taxonomic studies of the genus Neotoma have been completed in recent years, no genetic analyses or further systematic revisions of the species N. fuscipes have been published since Hoopers (1938) report.

Description.-- The riparian woodrat (Figure 60) is a medium-sized (200 to 400 grams; 7.05 to 14.11 ounces) rodent with a stockier build and a tail that is well furred (Hooper 1938, Williams et al. 1992) and not scaled, compared to the coexisting, nonnative roof or "black" rats (Rattus rattus).

Identification.-- N. f. riparia differs from other, adjacent subspecies of woodrats by being larger, lighter, and more grayish in color, with hind feet white instead of dusky on their upper surfaces, and a tail more distinctly bicolored (lighter below contrasting more with the darker dorsal color) (Hooper 1938).

Figure 60. Illustration of a riparian woodrat. Drawing by Wendy Stevens (© CSU Stanislaus Foundation).

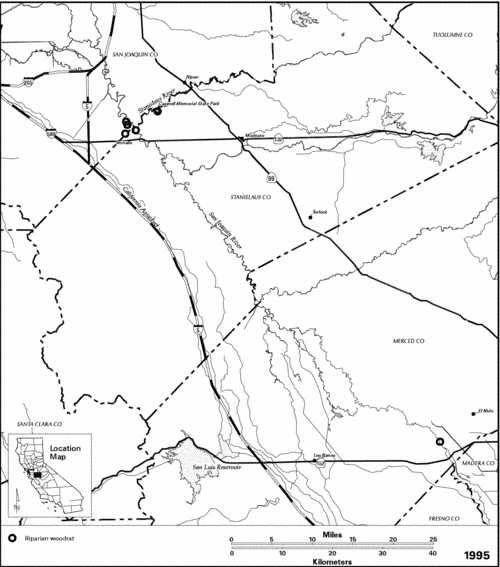

Historical Distribution.-- The type locality for the riparian woodrat is Kincaids Ranch, about 3 kilometers (2 miles) northeast of Vernalis in Stanislaus County, California (Figure 61). Hoopers (1938, p. 223) taxonomic analysis used only seven specimens, all from the vicinity of the type locality, but he believed that "it probably ranges south, along the river bottom lands, as far as southern Merced County or northern Fresno County, since the same environmental conditions evidently prevail throughout this area." Hooper further pointed out that the range of the riparian woodrat was disjunct by 1938 because no suitable habitat remained between the type locality and the San Francisco East Bay region, where two other subspecies (N. f. perplexa and N. f. annectens) could be found. Hall and Kelson (1959) assigned a specimen from El Nido, Merced County to this subspecies on the basis of geography.

Current Distribution.-- The range of the riparian woodrat is far more restricted today than it was in 1938 (Williams 1986). The only population that has been verified is the single, known extant population restricted to about 100 hectares (250 acres) of riparian forest on the Stanislaus River in Caswell Memorial State Park (Figure 61). Williams (1993) estimated the size of this population at 437 individuals. Analysis of California Department of Water Resources land use maps indicate that there were approximately 20 hectares (50 acres) of "natural vegetation" present along the San Joaquin River near the type locality in 1988, though no woodrats have been seen in that area. Today there is no habitat for woodrats around El Nido, which is located about 8.9 kilometers (5.5. miles) east of the San Joaquin River, the closest possible riparian habitat.

Figure 61. Distributional records for the riparian woodrat (Neotoma fuscipes riparia)

Food and Foraging.-- Although some species have more specialized diets than others (e.g., Stephens woodrat, N. stephensi, feeds almost exclusively on juniper), woodrats are, for the most part, generalist herbivores. They consume a wide variety of nuts and fruits, fungi, foliage and some forbs (Linsdale and Tevis 1951).

Behavior and Species Interactions.-- Dusky-footed woodrats live in loosely-cooperative societies and have a matrilineal (mother-offspring associations; through the maternal line) social structure (Kelly 1990). Unlike males, adjacent females are usually closely related and, unlike females, males disperse away from their birth den and are highly territorial and aggressive, especially during the breeding season. Consequently, populations are typically female-biased and, because o pronounced polygyny (mating pattern in which a male mates with more than one female in a single breeding season), the effective population size (i.e., successful breeders) is generally much smaller than the actual population size (Kelly 1990).

Habitat and Community Associations.-- Dusky- footed woodrats inhabit evergreen or live oaks and other thick-leaved trees and shrubs (Kelly 1990, Williams et al. 1992). Riparian woodrats are common, however, where there are deciduous valley oaks, but few live oaks. They are most numerous where shrub cover is dense and least abundant in open areas. In riparian areas, highest densities of woodrats and their houses are often encountered in willow thickets with an oak overstory (Linsdale and Tevis 1951).

Dusky-footed woodrats are well known for their large terrestrial stick houses, some of which can last for 20 or more years after being abandoned (Linsdale and Tevis 1951, Carraway and Verts 1991). At Caswell Memorial State Park, riparian woodrats also make houses of sticks and other litter (Williams 1993). At the Hastings Reserve, Monterey County, dusky-footed woodrat houses range from 60 centimeters (2 feet) to 150 centimeters (5 feet) in height, and can be 120 centimeters (4 feet) to 240 centimeters (8 feet) in basal diameter. Houses typically are placed on the ground against or straddling a log or exposed roots of a standing tree and are often located in dense brush. Nests also are placed in the crotches and cavities of trees and in hollow logs. Sometimes tree nests are constructed but this behavior seems to be more common in habitat with evergreen trees such as live oak (Williams et al. 1992).

Reasons for Decline.-- Although there is still no good estimate of the amount of riparian habitat remaining in the San Joaquin Valley, it is only a vestige of what it was 50 to 100 years ago. Thus, loss and fragmentation of habitat are the principal reasons for the decline of the riparian woodrat. Much of this loss was the result of the construction of large dams and canals which diverted water for the irrigation of crops and permanently altered the hydrology of Valley streams. More was lost through cultivation of the river bottoms. Historically, cattle also probably impacted riparian woodrat populations since the thick undergrowth, which is particularly important to woodrats, is sensitive to trampling, browsing and grazing by livestock.

Threats to Survival.-- The only known extant population of riparian woodrat is small, with its size limited by the available habitat. It is thus at an increased risk of extinction because of genetic, demographic, and random catastrophic events (e.g., drought, flooding, fire) that threatens small, isolated populations. Because of its breeding behavior, the effective size of woodrat populations is generally much smaller than the actual population size. This increases the risk of inbreeding depression.

The woodrat population at Caswell Memorial State Park is vulnerable to flooding of the Stanislaus River. Because of its well-developed arboreality (ability to climb in trees), the woodrat itself is not as sensitive to flooding as some other brush-dwelling species (e.g., the riparian brush rabbit). However, woodrat houses are essential for survival and these can be severely impacted by flooding, thus affecting population viability.

Conservation Efforts.-- The riparian woodrat was proposed for listing by the USFWS on November 21, 1997 (USFWS 1997). Although the only known population has some protection by residing in Caswell Memorial State Park, there are currently no conservation efforts underway specifically to benefit the riparian woodrat. The California Department of Parks and Recreation, however, has supported some general small-mammal studies and studies on the woodrat population at Caswell (Cook 1992, Williams 1993).

Conservation Strategy.-- Unlike many other sensitive species in the San Joaquin Valley, the life history of the riparian woodrat is particularly well known through studies on other subspecies of the dusky-footed woodrat, particularly N. f. luciana (Linsdale and Tevi 1951, Kelly 1990). However, using this information to develop a conservation plan is hampered by a lack of data on the current status and distribution of the species. Thus, surveys along all river corridors throughout its historical range to identify and map remaining riparian habitat and extant woodrat populations, if any are found, must be a primary element of a conservation strategy for the riparian woodrat.

Any conservation strategy for the riparian woodrat should focus on a long-term goal of reducing the effects of population fragmentation by establishing, wherever possible, linkages (corridors) between remnants of riparian habitat. If additional riparian woodrat populations are discovered by surveys, priority should be given to connecting occupied habitat patches. However, if no additional populations are found, then convenient or logical fragments will have to be reconnected and reintroduction of the species will be an important component of the conservation strategy.

Because much of the river bottom land in the San Joaquin Valley is in private ownership, a concerted outreach effort must be made to enlist the help of landowners in the conservation of riparian woodrats and their habitat. Through progressive habitat conservation plans and other existing programs (e.g., Riparian Habitat Joint Venture, Partners for Wildlife Program, and the evolving "safe-harbor" concept), incentives must be provided to encourage the establishment or restoration of riparian habitat.

All these conservation activities will depend on the understanding and receptivity of private landowners. Many of the private parcels of potential habitat for riparian woodrats on the Stanislaus and lower San Joaquin Rivers have federally-owned wildlife habitat and flood easements, administered by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (COE). This is true of the entire riparian corridor of the Stanislaus River downstream from Caswell Memorial State Park in Stanislaus and San Joaquin Counties. The COE must diligently inspect parcels with wildlife easements and ensure that the requirements of those easements are being met. Beyond that, the development of an effective outreach and incentive program focused on the owners of riparian lands is a critical and early step of any conservation strategy.

Conservation of the riparian woodrat may be furthered by changes in the management of National Wildlife Refuges in the San Joaquin Valley that will make these refuges more hospitable to riparian species. Such changes are specifically needed to help recover the riparian brush rabbit (as discussed elsewhere in this plan) and the woodrat.

Conservation Actions.-- Conserving the riparian woodrat depends on good information on status and distribution and sufficient protected habitat. To achieve these goals requires these actions:

- A survey and mapping of all riparian areas along the San Joaquin River and its major tributaries is of the highest priority. A cost-effective survey can be carried out through a combination of aerial photo interpretation, selective truthing of photos on the ground, and judicious trapping where permission is required and given.

- Develop in collaboration with owners of riparian land and local levee-maintenance districts an incentive program for preserving cover and riparian vegetation.

- Develop a plan for the restoration of riparian habitat, the establishment of riparian corridors, and the reintroduction, if necessary, of riparian woodrats to suitable habitat.

- Initiate a genetic study of the Caswell Memorial State Park woodrats, and any other riparian woodrat populations that can be samped, to determine inbreeding levels; and devise a procedure for ensuring that translocations neither reduce genetic diversity in the parent population nor unduly restrict it in the translocated population.

- Establish conservation agreements with willing landowners that do not already have conservation easements, as appropriate and necessary, to accomplish habitat restoration, linkage, and reintroduction goals.

- Begin efforts to restore and link riparian habitat, and reintroduce woodrats, as appropriate.

Although the timing of these management actions may depend on the development of additional information through surveys, some combination of actions will almost certainly be necessary for conservation. Therefore to the extent possible, planning for such action should go forward along with surveys. Then appropriate management action can follow without delay when surveys are finished.