Endangered Species Recovery Program | |

|

Home | News | Publications | Species profiles | Data and maps | About | Staff | Links | Department of Biological Sciences | CSU Stanislaus |

Recovery Plan for Upland Species of the San Joaquin Valley, California

Contents

. Introduction

. Species accounts

. Recovery

. Stepdown

. Implementation

. References

. Appendix

3. Short-Nosed Kangaroo Rat (Dipodomys nitratoides brevinasus)

- Taxonomy

- Description

- Identification

- Historical Distribution

- Current Distribution

- Food and Foraging

- Reproduction and Demography

- Behavior and Species Interactions

- Activity Cycles

- Habitat and Community Associations

- Reasons for Decline

- Threats to Survival

- Conservation Efforts

- Conservation Strategy

- Conservation Actions

Taxonomy.-- The short-nosed kangaroo rat is one of three subspecies of the San Joaquin kangaroo rat. The type specimen of D. n. brevinasus was collected in 1918 from Hays Station on the upper alluvial fan of Panoche Creek, Fresno County, California (Grinnell 1920). Hafner (1979), using discriminant analysis, reaffirmed conclusions of earlier researchers that populations of D. nitratoides on the Carrizo Plain and west of the Kern River alluvial fan, at the northwestern edge of Buena Vista Lake, and west of the channels, sloughs, and lakes fed by the Kern River were short-nosed kangaroo rats. Also, these waters at the west edge of the Valley floor marked the boundary between the subspecies brevinasus and nitratoides. The California Aqueduct closely follows this boundary from the Buena Vista Lake bed west of Lost Hills.

Description.-- See account of the Fresno kangaroo rat for a general description of the species. Adult short-nosed kangaroo rats average larger in size than Tipton and Fresno kangaroo rats. Mean mass is about 39 to 44 grams (1.4 to 1.6 ounces), head and body length averages about 100 to 110 millimeters (3.9 to 4.3 inches), and tail length about 115 to 130 millimeters (4.5 to 5.1 inches).

Identification.-- See the Fresno kangaroo rat account for ways to distinguish short-nosed kangaroo rats from other co-occurring species. The short-nosed kangaroo rat can be distinguished from the Fresno kangaroo rat by its larger average measurements: mean total length for males in different populations, 238 to 252 millimeters (9.4 to 9.9 inches); for females, 232 to 246 millimeters (9.1 to 9.7 inches); mean length of hind foot for males, 35.7 millimeters (1.41 inches); for females, 34.5 millimeters (1.36 inches); mean inflation of the auditory bullae for males, 22.6 millimeters (0.89 inch); for females, 22.4 millimeters (0.88 inch) (Hoffmann 1975) (see accounts of Fresno and Tipton subspecies for corresponding average measurements).

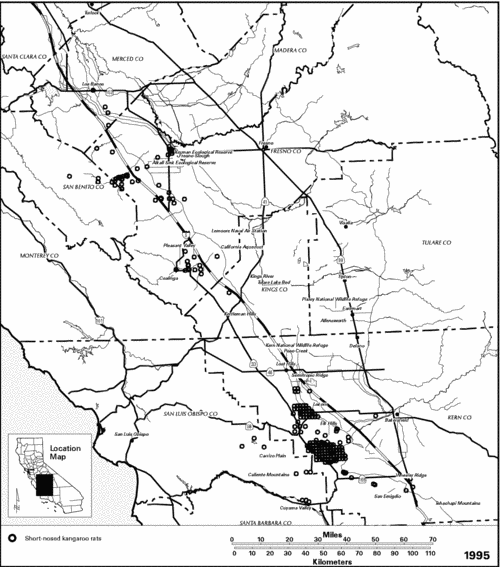

Historical Distribution.-- The historical geographic range of short-nosed kangaroo rats is only partly known from museum and literature records and recent studies at a few sites. There has not been a comprehensive study to define historical distribution, but the inhabited area was greater than 1,000,000 hectares (2,471,044 acres). Short-nosed kangaroo rats occupied arid grassland and shrubland associations along the western half of the Valley floor and hills on the western edge of the Valley from about Los Banos, Merced County, south to the foothills of the Tehachapi Range and extending east and northward inland above the edge of the Valley floor to about Poso Creek, north of Bakersfield (Figure 58). They also occurred on the Carrizo Plain and the upper Cuyama Valley (Grinnell 1920, 1922, Boolootian 1954, Hoffmann 1974, Hall 1981, Williams and Kilburn 1992, Williams et al. 1993b, Hafner 1979, Williams 1985).

Current Distribution.-- Current occurrences are incompletely known because there has not been a comprehensive survey for the species. Yet relatively intensive trapping surveys at several historically occupied sites with extant natural communities show that populations mostly are small, fragmented, and widely scattere. Recent large-scale survey and trapping efforts include: the Panoche Region of Fresno and San Benito Counties (D.F. Williams unpubl. data, Endangered Species Recovery Program unpubl. data); Cantua Creek, Fresno County (Williams et al. 1995, Williams and Tordoff 1988); the Kettleman Hills, Kings County (Williams et al. 1988); western Kern County (Anderson et al. 1991, EG&G Energy Measurements 1995a,b); Carrizo Plain Natural Area (Vanderbilt and White 1992, Williams et al. 1993b, Endangered Species Recovery Program unpubl. data); and Cuyama Valley (Endangered Species Recovery Program unpubl. data). Populations are known from around the edge of Pleasant Valley (Coalinga area), Fresno County; a few, scattered spots in the Kettleman and Lost Hills, Kings and Kern Counties; the Lokern, Elk Hills, San Emigdio, and Wheeler Ridge regions of western Kern County; the Carrizo Plain Natural Area; and the Caliente Mountains at the north edge of the Cuyama Valley.

Occupied habitats for areas known to support short-nosed kangaroo rats have not been completely mapped, and there are relatively large areas that offer potential habitat for the species that have not been surveyed. However, because only a few thousand acres of historical habitat on the Valley floor remain undeveloped, and this species occupies many of the same general areas occupied by giant kangaroo rats, but with a different pattern of habitat use, the extant occupied area is unlikely to be more than about 12,000 to 15,000 hectares (30,000 to 37,000 acres)--it is probably considerably less. The larger estimate represents about 1.5 percent of the estimated historical habitat. Even if there was twice this amount of currently occupied habitat and only 80 percent as much historical habitat, the currently occupied area only would be about 3.75 percent of historical habitat.

Figure 58. Distributional records for the short-nosed kangaroo rat (Dipodomys nitratoides brevinasus)

Food and Foraging.-- Short-nosed kangaroo rats have essentially the same diet and foraging behavior as the other subspecies of the San Joaquin kangaroo rat (Eisenberg 1963).

Reproduction and Demography.-- Captive-bred short-nosed kangaroo rats had a gestation period of 32 days and an average litter size of 2.3 (mode = 2). Litter mass at birth averaged 7.6 grams (0.27 ounce). Females showed a postpartum (soon after giving birth) estrus (Eisenberg and Issac 1963). In captivity, a young female conceived at 12 weeks of age and produced two young (Eisenberg and Issac 1963).

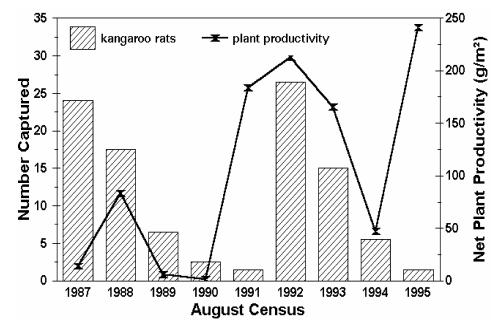

The reproductive season at higher elevations, such as on the Carrizo Plain Natural Area, is about 2 to 3 months shorter than on the Valley floor (see Tipton kangaroo rat account), with estrus commencing in late February or March and ending by May most years, though reproduction may continue through August in years with a prolonged wet spring. Most females appear to have only a single litter, and young-of-the-year females appear to have reproduced only when there is a prolonged wet season (Williams et al. 1993b, Williams and Nelson in press, Endangered Species Recovery Program unpubl. data). Like other subspecies of the San Joaquin kangaroo rat, populations of the short-nosed kangaroo rat undergo dramatic population fluctuations, and sometimes disappear from an area (Williams et al. 1993b, Endangered Species Recovery Program unpubl. data). On the Elkhorn Plain, the population has fluctuated, primarily in response to varying rainfall and plant productivity (Figure 59).

Figure 59. Number of short-nosed kangaroo rats captured during August censuses, Elkhorn Plain

Behavior and Species Interactions.-- Behavior of short-nosed kangaroo rats was studied extensively in the laboratory and compared to other members of the family Heteromyidae (Eisenberg 1963). Individuals usually live solitarily except when females are in estrus and tolerate the presence of a male.

Species interactions are essentially the same as for the Fresno and Tipton subspecies. Short-nosed kangaroo rats can coexist with giant kangaroo rats only where there are scattered shrubs, and on the periphery of giant kangaroo rat colonies on relatively steep, rocky slopes (Williams and Tordoff 1988).

Activity Cycles.-- Short-nosed kangaroo rats are nocturnal and active year roun. They do not become dormant. They frequently appear above ground shortly after sunset and before dark (Tappe 1941, D. F. Williams unpubl. data). They were not captured in the morning hours after sunrise on the Elkhorn Plain, but were taken in the evening before sunset (Williams and Tordoff 1988). In captivity, short-nosed kangaroo rats showed no difference in activity under simulated full-moon and new-moon conditions (Lockart and Owings 1974).

Habitat and Community Associations.-- Short- nosed kangaroo rats historically were found mostly on flat and gently sloping terrain and on hilltops in desert-shrub associations, primarily saltbushes and California ephedra. On the western slopes of the Temblor Range, San Luis Obispo County, they also occur sparingly on steep, rocky hillsides among chaparral yucca, ephedra, and other shrubs, up to about 840 meters (2,750 feet) (Vanderbilt and White 1992, Williams and Tordoff 1988, D.F. Williams unpubl. data). On the Elk Hills Naval Petroleum Reserves in California, they are most abundant on flatter terrain with shrub densities between about 0.1 and 0.17 per square meter (0.1 to 0.2 per square yard), as opposed to hilly terrain with higher shrub densities (EG&G Energy Measurements 1995a,b).

Short-nosed kangaroo rats generally occupy grassland with scattered shrubs and desert-shrub associations on friable soils. They inhabit highly saline soils around Soda Lake, on the Carrizo Plain, and less saline soil elsewhere. On the Valley floor, south of Los Banos, Merced County, small populations, whose taxonomic identity is uncertain (exilis or brevinasus) live on levees secure from winter flooding, then move into seasonally flooded iodine bush shrublands during the summer months, where at least some individuals reproduce (Johnson and Clifton 1992). In the Panoche Valley, San Benito County, short-nosed kangaroo rats are found on gentle slopes and rolling, low hilltops where some shrubs are present (Hawbecker 1951). Over most of their current range they are generally more numerous in lighter, friable soils such as the sandy bottoms and banks of arroyos and other sandy areas (Williams and Tordoff 1988, D.F. Williams unpubl. data).

Reasons for Decline.-- The main cause for decline of short-nosed kangaroo rats was the extensive agricultural developments of the 1960s through 1970s within their range, made possible by the Central Valley and State Water projects. Loss of the best habitats and the largest populations they supported, together with fragmentation and isolation, and subsequent random catastrophic events (e.g., drought, flooding, fire), have apparently caused their elimination from some sites still undeveloped. In limited areas, widespread broadcasting of rodenticides to control California ground squirrels (and sometimes kangaroo rats) may have contributed to elimination of some populations (Williams and Kilburn 1992).

Threats to Survival.-- Current and potential threats cannot be adequately assessed without a more complete understanding of current distribution and population statuses. Yet, from what is known of the biology of the species, the greatest threats probably are random catastrophic events (e.g., drought, flooding, fire) and inappropriate habitat management. Short-nosed kangaroo rats appear to be particularly sensitive to buildup of too much plant material when grazing or other land uses that reduce plant cover and mulch accumulation are curtailed. They also may be harmed by overstocking range land, especially when it results in heavy browsing and death of shrubs. Fires that destroy saltbushes may reduce habitat quality for the species. These factors probably vary, with lack of grazing or other vegetation management being less important or unimportant in the most arid portions of its range and most important in the wettest.

The largest existing population of short-nosed kangaroo rats is in western Kern County in the Lokern and Elk Hills region. Though several thousand acres are in public ownership, relatively little of it is adequately protected by title or statute. Privatization of the Naval Petroleum Reserve #1 at Elk Hills could lead to greaer surface disturbance if rates of exploration and production are increased. Unless a substantial proportion of the occupied habitat can be protected from development and the habitat managed by appropriate land uses, additional habitat fragmentation and habitat degradation could lead to extinction of this population by random catastrophic events (e.g., drought, flooding, fire).

Elsewhere, the only other sizable population is on the Carrizo Plain Natural Area. Though much of this is now in public ownership, between one-third and one-half of the land in the Natural Area has not been grazed since acquisition. Another several thousand acres had been cultivated since at least the 1930s, some longer, and 0.1 to 1.0 meter (0.3 to 3 feet) of topsoil were lost during that time (R. van de Hoek pers. comm., D.F. Williams unpubl. observ.). Cultivation ceased on most parcels between 1987 and 1989. Whether or not short-nosed kangaroo rats have recolonized any of the ground retired since is not known. Much of it may have lost too much soil to provide suitable habitat for this species.

On the Carrizo Plain Natural Area, lack of grazing in years of high plant productivity or other appropriate habitat management poses an unknown level of threat to conserving short-nosed kangaroo rats. Though inappropriate management probably would not result directly in elimination from the Natural Area, it probably would prevent the species population from reaching a size and distribution that would adequately insulate it from the negative effects of random catastrophic events (e.g., drought, flooding, fire).

Conservation Efforts.-- The short-nosed kangaroo rat has no protected status. It was removed as a Category 1 candidate for Federal listing in 1995 (USFWS 1995b), and is now considered a species of concern (USFWS 1996). Though little direct conservation action has been taken for this species, it has benefited from surveys and avoidance of impacts on Federal property (EG&G Energy Measurements 1995a,b); land purchases for the Carrizo Plain Natural Area by the State and Federal governments; and from land purchases for mitigation and nonmitigation in the Sand Ridge area (The Nature Conservancy), Lokern area (California Energy Commission, The Nature Conservancy, USBLM, CDFG), and possibly elsewhere in the Coalinga-Panoche regions of Fresno and San Benito Counties (Table 2). The short-nosed kangaroo rat also has benefited from the California Energy Commissions Ecosystem Protection Program surveys and plans for the Southern San Joaquin Valley (Anderson et al. 1991), and its Biological Resources Inventory of the Carrizo Plain Natural Area (Kakiba-Russell et al. 1991).

The Bird and Mammal Conservation Program of the CDFG, USBLM, Bureau of Reclamation, and Service collectively have supported research on population ecology and grazing impacts of kangaroo rats on the Elkhorn Plain that has provided information on the population dynamics of short-nosed kangaroo rats (Williams et al. 1993b, Williams and Nelson in press, Endangered Species Recovery Program unpubl. data). Other important information has been gathered by EG&G Energy Measurements (1995a,b) for the U.S. Department of Energy during their small mammal monitoring and habitat relationships studies on the Naval Petroleum Reserves in California, and the California Energy Commissions small mammal monitoring program in the Lokern Region (Anderson et al. 1991).

Conservation Strategy.-- The short-nosed kangaroo rat will benefit from a detailed investigation of current distribution and population status, a population monitoring program, appropriate habitat management, and habitat protection, particularly in western Kern County, but probably also in the Panoche Region. Habitat management prescriptions are likely to differ on the Carrizo Plain Natural Area from those in western Kern County, and studies to determine appropriate land use and vegetation management regimes are needed in both areas, and probably elsewhere. The long-term protection of natural land in the Elk Hills Naval Petroleum Reserves in California and the Lokern Area are necessary to improve the status of the spcies. Determining the causes and stopping or reversing the decline in short-nosed kangaroo rat populations in western Kings and Fresno Counties and eastern San Benito County also are elements of conservation. A final component of the conservation strategy for this species is to restore and reintroduce short-nosed kangaroo rats to lands retired from irrigated agriculture because of drainage problems. Ideally one or more major blocks of retired land can be connected by continuous habitat along major intermittent stream channels to the natural land in the Panoche region.

Three main constituents of a conservation strategy for short-nosed kangaroo rats are:

- Determining how to enhance habitat for short- nosed kangaroo rats that lessens the severity of cyclic population declines.

- Consolidating and protecting blocks of suitable habitat for short-nosed kangaroo rats in western Kern, Kings, and Fresno Counties.

- Restoring habitat for short-nosed kangaroo rats on farmland retired because of drainage problems.

Retired land ideally should be of several thousand acres each, minimally about 2,330 hectares (5,760 acres) with a core of at least 800 hectares (about 2,000 acres) of high quality habitat that is not subject to periodic flooding from overflowing streams or sheet flooding from torrential rain. They should provide topographic and biotic diversity. The vegetation should be actively managed by an appropriate level of livestock grazing to prevent excessive accumulation of mulch and growing plants until such time as optimum management conditions are determined by scientific research. Large, relatively square blocks will minimize edge with agricultural lands and the consequent pest problems at the agricultural interface.

Conservation Actions.-- Needed to conserve short- nosed kangaroo rats, in priority of implementation, are:

- Initiate and coordinate habitat management studies for short-nosed kangaroo rats at sites representing the range of existing habitat conditions for the species, in the Carrizo Plain Natural Area, Lokern / Elk Hills region, and western Fresno County.

- Protect existing habitat for short-nosed kangaroo rats in the Naval Petroleum Reserves in California, Lokern area, and elsewhere in the region.

- Design and implement a range-wide population monitoring program that measures population and environmental fluctuations at sites representative of the range of sizes and habitat conditions for the species.

- Inventory and assess existing natural land within the historical range of the short-nosed kangaroo rat to assess population status.

- Develop and implement research on restoration of habitat for short-nosed kangaroo rats on retired irrigated land.

- Include habitat needs of short-nosed kangaroo rats in any plans by government to acquire and restore drainage-problem lands within its historical geographic range, particularly western Fresno County.

- Restore habitat on retired agricultural lands as needed.

- Reevaluate the status of the short-nosed kangaroo rat within 3 years of recovery plan approval.