Endangered Species Recovery Program | |

|

Home | News | Publications | Species profiles | Data and maps | About | Staff | Links | Department of Biological Sciences | CSU Stanislaus |

Recovery Plan for Upland Species of the San Joaquin Valley, California

Contents

. Introduction

. Species accounts

. Recovery

. Stepdown

. Implementation

. References

. Appendix

K. Blunt-Nosed Leopard Lizard (Gambelia sila)

- 1. Description and Taxonomy

- 2. Historical and Current Distribution

- 3. Life History and Habitat

- 4. Reasons for Decline and Threats to Survival

- 5. Conservation Efforts

- 6. Recovery Strategy

1. Description and Taxonomy

Taxonomy.-- The blunt-nosed leopard lizard was described and named by Stejneger (1890) as Crotaphytus silus, from a specimen collected in Fresno, California. Cope (1900), however, considered the blunt-nosed leopard lizard to be a subspecies of the long-nosed leopard lizard (C. wislizenii), and listed it as C. w. silus. Under this arrangement, leopard lizards and collared lizards were placed in the same genus. Smith (1946) separated the collared from the leopard lizards, placing the latter in the genus Gambelia. The bases for separation were differences in head shape, presence or absence of gular (throat area) folds, and differences in bony plates on the head. The subspecific status of G. w. silus was retained by Smith (1946). This generic split was not universally agreed upon and the status, both generic and specific, of the lizards remained controversial until Montanucci (1970) presented a solid argument for specific status based upon the study of hybrids between the long-nosed and blunt-nosed leopard lizards. Montanucci et al. (1975) again separated Gambelia from Crotaphytus, resulting in the name Gambelia silus (Jennings 1987). Frost and Collins (1988), Collins (1990), and Germano and Williams (1993) used the spelling sila to properly agree in gender with the genus Gambelia.

Description.-- The blunt-nosed leopard lizard (Figure 48) is a relatively large lizard of the family Iguanidae, with a long, regenerative tail; long, powerful hind limbs; and a short, blunt snout (Smith 1946, Stebbins 1985). Adult males are larger than adult females, ranging in size from 87 to 120 millimeters (3.4 to 4.7 inches) snout-vent length (Tollestrup 1982). From snout to vent, females are 86 to 111 millimeters long (3.4 to 4.4 inches). Adult males weigh between 31.8 and 37.4 grams (1.3 to 1.5 ounces), and adult females weigh between 20.6 and 29.3 grams (0.8 to 1.2 ounces) (Uptain et al. 1985). Males are distinguished from females by their enlarged postanal scales, femoral pores (visible pores on the underside of the thigh), temporal and mandibular muscles (muscles on the skull that close the jaws), and tail base (Montanucci 1965).

Although blunt-nosed leopard lizards are darker than other leopard lizards, they exhibit tremendous variation in color and pattern on the back (Tanner and Banta 1963, Montanucci 1965, 1970). Background color ranges from yellowish or light gray-brown to dark brown depending on the surrounding soil color and vegetation association (Smith 1946, Montanucci 1965, 1970, Stebbins 1985). The under surface is uniformly white.

The color pattern on the back consists of longitudinal rows of dark spots interrupted by a series of from 7 to 10 white, cream-colored, or yellow transverse bands. In the blunt-nosed leopard lizard, the cross bands are much broader and more distinct than in other leopard lizards and extend from the lateral folds on each side to the middle of the back, where they meet or alternate along the midline of the back. With increasing age the cross bands may fade and the spots may become smaller and more numerous, particularly in males Montanucci 1967, Smith 1946). Similarly colored bands or rows of transverse spots produce a banded appearance to the tail (Smith 1946). Juveniles have blood-red spots on the back that darken with age, becoming brown when sexual maturity is reached, although a few adults retain reddish centers to the spots (Montanucci 1967).

Except for the throat, undersides are uniformly white to yellow in immature lizards and prenuptial females. Nuptial females have bright red-orange markings on the sides of the head and body and the undersides of the thighs and tail. This color fades to pink or light orange by late July. Males in many populations develop a nuptial color during the breeding season that spreads over the entire undersides of the body and limbs. This salmon to bright rusty-red color may be maintained indefinitely (Montanucci 1965).

Identification.-- The blunt-nosed leopard lizard can be distinguished from the long-nosed leopard lizard by its color pattern, truncated snout, and short, broad triangular head (Stejneger 1890, Smith 1946). The blunt-nosed leopard lizard has dark blotches on the throat instead of parallel streaks of the long-nosed leopard lizard. Other distinguishing characteristics are a significantly smaller number of maxillary and premaxillary teeth (this may be directly related to the shortened snout) and a smaller variation in the number of femoral pores (Smith 1946). In general, blunt-nosed leopard lizards can be distinguished from all other leopard lizards by their retention into adulthood of the primitive color pattern shared by all young leopard lizards (absence of ornamentation around the dorsal spots; retention of wide, distinct cross bands; presence of gular blotches; and fewer spots arranged in longitudinal rows) (Smith 1946, Montanucci 1970).

Figure 48. Illustration of a blunt-nosed leopard lizard. Drawing by Kristina Bocchini (© by CSU Stanislaus Foundation).

2. Historical and Current Distribution

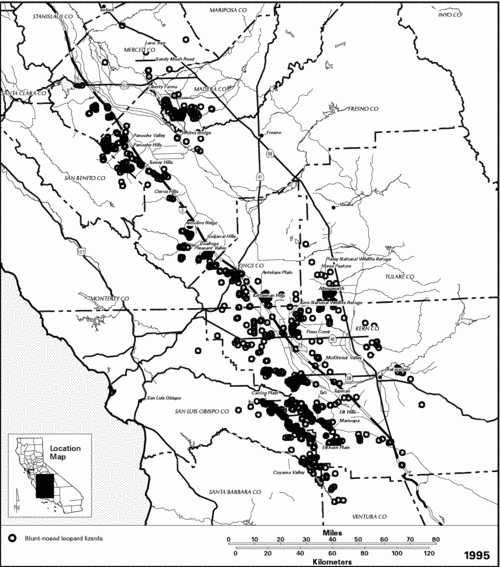

Historical Distribution.-- The blunt-nosed leopard lizard is endemic to the San Joaquin Valley of central California (Stejneger 1893, Smith 1946, Montanucci 1965, 1970, Tollestrup 1979a). Although the boundaries of its original distribution are uncertain, blunt-nosed leopard lizards probably occurred from Stanislaus County in the north, southward to the Tehachapi Mountains in Kern County (Figure 49). Except where their range extends into the Carrizo Plain and Cuyama Valley west of the southwestern end of the San Joaquin Valley, the foothills of the Sierra Nevada and Coast Range Mountains, respectively, define the eastern and western boundaries of its distribution. The blunt-nosed leopard lizard is not found above 800 meters (2,600 feet) in elevation (Montanucci 1970). The blunt-nosed leopard lizard hybridizes with the long-nosed leopard lizard where their ranges meet in Ballinger Canyon and others (Santa Barbara and Ventura Counties) in the Cuyama River watershed (Montanucci 1970, Le Fevre in litt. 1976).

Current Distribution.-- Although the blunt-nosed leopard lizard has been listed as endangered for 30 years, there has never been a comprehensive survey of its entire historical range. The currently known occupied range of the blunt-nosed leopard lizard is in scattered parcels of undeveloped land on the Valley floor, and in the foothills of the Coast Range. Surveys in the northern part of the San Joaquin Valley documented the occurrence of the blunt-nosed leopard lizard in the Firebaugh and Madera Essential Habitat Areas (Williams 1990). Essential Habitat Areas were defined in previous recovery plan editions for this species as undeveloped wildlands containing suitable habitat for the blunt-nosed leopard lizard and essential to the continued survival of the species (USFWS 1980a, in litt. 1985).

In the southern San Joaquin Valley, extant populations are known to occur on the Pixley National Wildlife Refuge, Liberty Farms, Allensworth, Kern National Wildlife Refuge, Antelope Plain, Buttonwillow, Elk Hills, and Tupman Essential Habitat Areas, on the Carrizo and Elkhorn Plains, north of Bakersfield around Poso Creek, and in western Kern County in the area around the towns of Maricopa, McKittrick, and Tft (Byrne 1987, R.L. Anderson pers. comm., L.K. Spiegel pers. comm.). Personal observations by D.J. Gemano have been made at the Kern Front oil field, at the base of the Tehachapi Mountains on Tejon Ranch, and just west of the California Aqueduct on the Tejon and San Emizdio Ranches (D.J. Gemano, pers. comm.). Remaining undeveloped lands farther north that support blunt-nosed leopard lizard populations include the Ciervo, Tumey, and Panoche Hills, Anticline Ridge, Pleasant Valley, and the Lone Tree, Sandy Mush Road, Whitesbridge, Horse Pasture, and Kettleman Hills Essential Habitat Areas (CDFG 1985; Figure 49). The species is presumed to be present still in the upper Cuyama Valley, though no recent inventory is known for that area.

Figure 49. Distributional records for the blunt-nosed leopard lizard (Gambelia sila)

3. Life History and Habitat

Food and Foraging.-- Blunt-nosed leopard lizards feed primarily on insects (mostly grasshoppers, crickets, and moths) and other lizards, although some plant material is rarely eaten or, perhaps, unintentionally consumed with animal prey. They appear to feed opportunistically on animals, eating whatever is available in the size range they can overcome and swallow. Which lizards are eaten is largely determined by the size and behavior of the prey. Lizard species taken as prey include: side-blotched lizards (Uta stansburiana), coast horned lizards (Phrynosoma coronatum), California whiptails (Cnemidophorus tigris), and spiny lizards (Sceloporus spp.). Young of its own species also are eaten (Montanucci 1965, Kato et al. 1987a, Germano and Williams 1994a). Because they have similar diets, interspecific competition probably occurs between the blunt-nosed leopard lizard and California whiptail (Montanucci 1965, Tollestrup 1979b).

Reproduction and Demography.-- Breeding activity begins within a month of emergence from dormancy and lasts from the end of April through the beginning of June, and in some years to near the end of June. During this period, and for a month or more afterward, the adults often are seen in pairs and frequently occupy the same burrow systems (Montanucci 1965, Germano and Williams 1994b). Male territories may overlap those of several females, and a given male may mate with several females. Copulation may occur as late as June (Montanucci 1965).

Two to six eggs averaging 15.6 by 25.8 millimeters (0.6 by 1.0 inch) are laid in June and July, and their numbers are correlated with the size of the female (Montanucci 1967). Under adverse conditions, egg-laying may be delayed 1 or 2 months or reproduction may not occur at all (Montanucci 1965, Tollestrup 1979b, 1982, Germano et al. 1994). Eggs are laid in a chamber either excavated specifically for a nest or already existing within the burrow system (Montanucci 1965, 1967). Females typically produce only one clutch of eggs per year, but some may produce three or more under favorable environmental conditions (Montanucci 1967, USFWS 1985a, Germano and Williams 1992, Williams et al. 1993b). After about 2 months of incubation, young hatch from July through early August, rarely to September, and range in size from 42 to 48 millimeters (1.7 to 1.9 inches) snout-vent length (Montanucci 1965, Tollestrup 1982). Before their first winter, young leopard lizards may grow to 88 millimeters (3.5 inches) in snout-vent length (Montanucci 1967).

Sexual maturity is reached in from 9 to 21 months, depending on the sex and environmental conditions (USFWS 1985a). Females tend to become sexually mature earlier than males, breeding for the first time after the second dormancy, while males usually do not breed until later (Montanucci 1965, 1967).

The relative proportions of the three age groups (adult, subadult, hatchling or young-of-the-year) change through the activity season as young are added to the population only in August or later and entry into dormancy and differential mortality affects the proportions in age groups above ground. Data based upon surface activity do not give an accurate estimate of the population age structure becuse the adults cease activity above ground from about 4 weeks before to about the same time as the eggs hatch. The best estimate of the relative proportions of adults and subadults (animals hatched the previous summer) may be made from data gathered in May because both groups are active on the surface then. In May the proportions were 85 percent adults and 15 percent subadults (Montanucci 1965). Montanucci (1965) believed that data gathered in August for subadults and hatchlings yielded the best estimate of their proportions because both groups were active. His data were about 2:1 hatchlings to subadults. Combining these numbers, the population consisted of about 67 percent adults, 11 percent subadults, and 22 percent hatchlings. The age structure of a population on Pixley National Wildlife Refuge consisted of 62 percent adults, 27 percent subadults, and 11 percent hatchlings in 1984 (Uptain et al. 1985).

Age structure of adults during a 7-year period on the Elkhorn Plain (Williams et al. 1993a, Endangered Species Recovery Program unpubl. data), was determined in 1995; percentages of 2, 3, 4, and 5 year-old males were 69.5, 21, 6.5, and 2, respectively. Percentages of females 2, 3, and 4 years old were 70, 22, and 7.5; none were recaptured older than 4 years. Parker and Pianka (1976) made estimates for the long-nosed leopard lizard based on their data for a Utah population, which are consistent with the age structure and reproductive situation described for the blunt-nosed leopard lizard. Maximum longevity would thus be 8 to 9 years with an annual survivorship of about 50 percent.

In several populations, and during most of the year, males appear to outnumber females by a ratio of 2:1 (Montanucci 1965, Uptain et al. 1985, Kato et al. 1987b). Mullen (1981) reported that the ratio of males to females was 3:1, whereas Montanucci (1965) found that the numbers in a Valley floor population were equal. Uptain et al. (1985) showed that, although 63 percent of the hatchlings in a population on Pixley National Wildlife Refuge were male, the male:female ratio varied seasonally from 2:1 in the spring, to 1:1 in the summer, and to 2:3 in the fall. These were all based on short-term studies. In contrast, populations on two plots on the Elkhorn Plain over several years typically had adult and subadult sex ratios of about 1:1 (1:1.04). Females outnumbered males more often than the reverse during census periods in May and June. Hatchling sex ratios, however, showed the opposite, with males outnumbering females, most censuses with ratios varying between about 1.5:1 and 2.5:1 male:female (Williams et al. 1993b, Germano and Williams 1994b, Endangered Species Recovery Program unpubl. data).

Male and female home ranges often overlap. The mean home range size varies from 0.1 to 1.1 hectares (0.25 to 2.7 acres) for females and 0.2 to 1.7 hectares (0.52 to 4.2 acres) for males (Tollestrup 1983, Kato et al. 1987b).

There are no current overall population size estimates for the species. Uptain et al. (1985) reported densities ranging from 0.3 to 10.8 lizards per hectare (0.1 to 4.2 per acre) for a population on the Pixley National Wildlife Refuge in Tulare County. In a previous study of this population, Tollestrup (1979) estimated an average density of 3.3 lizards per hectare (1.3 per acre). In 1991, after three previous years of severe drought, two 8.1-hectare (20-acre) plots had estimated densities of 6.7 and 7.0 lizards per hectare (2.7 and 2.8 per acre) on Pixley National Wildlife Refuge (Williams and Germano 1991). On the Elkhorn Plain, estimated population size on two 8.1-hectare plots of adult and subadult blunt-nosed leopard lizards in June (period of peak above-ground activity) varied between 0 in 1990 to more than 170 in 1993. Only subadult lizards were active above ground in April and no lizards were active by June 1990, the year of severest drought (Williams et al. 1993b, Germano et al. 1994, D. J. Germano and D.F. Williams unpubl. data). Turner et al. (1969) estimated that the average density of a southern Nevada population of the long-nosed leopard lizard was 3 lizards per hectare (1.2 per acre). Population densities in marginal habitat generlly do not exceed 0.5 blunt-nosed leopard lizards per hectare (0.2 per acre) (Mullen 1981, Le Fevre in litt. 1976, Madrone Associates 1979).

Behavior and Species Interactions.-- Social behavior is more highly developed in the blunt-nosed leopard lizard than in the long-nosed leopard lizard. For example, territorial defense and related behavioral activity are completely absent in the long-nosed leopard lizard, whereas blunt-nosed leopard lizards are highly combative in establishing and maintaining territories (Montanucci 1970). In addition, Tollestrup (1979, 1983) observed six distinct behavioral displays specific to the blunt-nosed leopard lizard. Behavioral displays of all types were more frequent during the breeding season.

Leopard lizards use small rodent burrows for shelter from predators and temperature extremes (Tollestrup 1979b). Burrows are usually abandoned ground squirrel tunnels, or occupied or abandoned kangaroo rat tunnels (Montanucci 1965). Each lizard uses several burrows without preference, but will avoid those occupied by predators or other leopard lizards. Montanucci (1965) found that in areas of low mammal burrow density, lizards will construct shallow, simple tunnels in earth berms or under rocks. While foraging, immature lizards also take cover under shrubs and rocks.

Potential predators of blunt-nosed leopard lizards include whipsnakes, gopher snakes, glossy snakes (Arizona elegans), western long-nosed snakes (Rhinocheilus lecontei), common king snakes, western rattlesnakes, loggerhead shrikes (Lanius ludovicianus), American kestrels (Falco sparverius), burrowing owls, greater roadrunners (Geococcyx californianus), golden eagles (Aquila chrysaetos), hawks, California ground squirrels, spotted skunks (Spilogale putorius), striped skunks (Mephitis mephitis), American badgers, coyotes, and San Joaquin kit foxes (Montanucci 1965, Tollestrup 1979b). Blunt-nosed leopard lizards are hosts to endoparasites such as nematodes, and ectoparasites such as mites and harvest mites (Montanucci 1965).

Activity Cycles.-- Seasonal above-ground activity is correlated with weather conditions, primarily temperature. Optimal activity occurs when air temperatures are between 23.5 degrees and 40.0 degrees Celsius (74 and 104 degrees Fahrenheit) and ground temperatures are between 22 degrees and 36 degrees Celsius (72 and 97 degrees Fahrenheit) (USFWS 1985a, J. Brode pers. comm.). Some activity has been observed at temperatures as high as 50 degrees Celsius (122 degrees Fahrenheit) (OFarrell and Kato 1980, Mullen 1981, Tollestrup 1976, Williams and Tordoff 1988). Body temperatures range from 32.2 to 42.0 degrees Celsius (90 and 108 degrees Fahrenheit) (Cowles and Bogert 1944, Mullen 1981). Because diurnal activity is temperature dependent, blunt-nosed leopard lizards are most likely to be observed in the morning and late afternoon during the hotter days (Tollestrup 1976). Smaller lizards and young have a wider activity range than the adults (Montanucci 1965). This results in the smaller, subadult lizards emerging from hibernation earlier than adults, remaining active later in the year, and being active during the day earlier and later than adults (Montanucci 1965). Adults are active above ground in the spring months from about March or April through June or July, with the amount of activity decreasing so that by the end of June or July almost all sightings are of subadult and hatchling leopard lizards (Williams et al. 1993b). Also, following the breeding season, the proportion of each sex active changes as males tend to cease surface activity sooner than females (Montanucci 1967, Williams and Tordoff 1988). Adults captured on the surface in August are about 70 percent females (Montanucci 1967). Adults retreat to their burrows to brummate (dormancy in poikilothermic vertebrates [having a body temperature that varies with the temperature of its surroundings]), beginning in August or September, but hatchlings are active until mid-October or November, depending on weather.

Habitat and Community Associations.-- Blunt-nosd leopard lizards inhabit open, sparsely vegetated areas of low relief on the San Joaquin Valley floor and in the surrounding foothills (Smith 1946, Montanucci 1965). On the Valley floor, they are most commonly found in the Nonnative Grassland and Valley Sink Scrub communities described by Holland (1986). The Valley Sink Scrub is dominated by low, alkali-tolerant shrubs of the family Chenopodiaceae, such as iodine bush, and seepweeds. The soils are saline and alkaline lake bed or playa clays that often form a white salty crust and are occasionally covered by introduced annual grasses. Prior to agricultural development, Valley Sink Scrub was widespread around Kern, Buena Vista, Tulare, and Goose lakes and extended north to the Sacramento Valley along the trough of the San Joaquin Valley. Today, nearly all the remaining Valley sink scrub on the Valley floor is seasonally flooded fragments of this historical community. This community corresponds to two that Tollestrup (1976) described as Allenrolfea grassland and Suaeda flat.

Valley Needlegrass Grassland, Nonnative (Annual) Grassland, and Alkali Playa (Holland 1986) also provide suitable habitat for the lizard on the Valley floor. Valley Needlegrass Grassland is dominated by native perennial bunchgrasses, including purple needlegrass (Nassella pulchra) and alkali sacaton. Associated with the perennial grasses are native and introduced annual plants. Both the Valley Needlegrass Grassland and Nonnative/Annual Grassland occur on fine-textured soils and probably were widespread in the Valley before large areas were converted to agriculture. The Alkali Playa community occurs on poorly drained, saline and alkaline soils in small, closed basins. The small, widely spaced, dominant shrubs include: iodine bush, saltbushes, and greasewood (Sarcobatus vermiculatus).

Blunt-nosed leopard lizards also inhabit Valley Saltbush Scrub, which is a low shrubland, with an annual grassland understory, that occurs on the gently sloping alluvial fans of the foothills of the southern San Joaquin Valley and adjacent Carrizo Plain. This community is dominated by the chenopod shrubs, common saltbush (Atriplex polycarpa) and spiny saltbush (Atriplex spinifera), and is associated with non-alkaline, sandy or loamy soils. Tollestrup (1976) described this plant community as Atriplex grassland. Similar to this community, but dominated principally by common saltbushes, are the Sierra-Tehachapi Saltbush Scrub (extending from the southern Sierra Nevada north of Porterville to the Grapevine in the Tehachapi Mountains) and Interior Coast Range Saltbush Scrub. The latter ranges from Pacheco Pass to Maricopa but, for the most part, has been converted by grazing and fire to Nonnative/Annual Grassland. Other foothill communities that occur within the range of the blunt-nosed leopard lizard are Upper Sonoran Subshrub Scrub and Serpentine Bunchgrass (Holland 1986). In general, leopard lizards are absent from areas of steep slope, dense vegetation, or areas subject to seasonal flooding (Montanucci 1965).

4. Reasons for Decline and Threats to Survival

Reasons for Decline.-- Since the 1870s and the advent of irrigated agriculture in the San Joaquin Valley, more than 95 percent of the original natural communities have been destroyed. This dramatic loss of natural communities was the result of cultivation, modification and alteration of existing communities for petroleum and mineral extraction, pesticide applications, off-road vehicle use, and construction of transportation, communications, and irrigation infrastructures. These processes collectively have caused the reduction and fragmentation of populations and decline of blunt-nosed leopard lizards (Stebbins 1954, Montanucci 1965, USFWS 1980a, 1985a, Germano and Williams 1993).

Farming began in the Valley as a direct response to increased demands for local food supplies, created by the migration of settlers to California during the 1849 Gold Rush (California Department of Water Resources 1974). Land conversion was accelerated in the 1920s with the advent of reiable electrical groundwater pumps and in the 1950s and 1960s with importation of water via Federal and State water projects (San Joaquin Valley Interagency Drainage Program 1979). By 1985, 94 percent of wildlands on the Valley floor had been lost to agricultural, urban, petroleum, mineral, or other development (USFWS 1985c, CDFG 1985).

Stebbins (1954) first recognized that agricultural conversion of its habitat was causing the elimination of the blunt-nosed leopard lizard. The cumulative effects of the dramatic decline in its available habitat and degradation of existing habitat by a variety of human activities have resulted in the lizards present status as endangered.

In the first blunt-nosed leopard lizard recovery plan (USFWS 1980a), 20 Habitat Units were identified as "Essential" to the continued survival of the blunt-nosed leopard lizard, though these did not have any legal protection equivalent to critical habitat. Ten of these habitat units were recommended as having priority for protection (USFWS 1980a, in litt. 1985). Between 1977 and 1985, over 30,000 hectares (74,000 acres) of this important Valley-floor habitat were destroyed.

Threats to Survival.-- Habitat disturbance, destruction, and fragmentation continue as the greatest threats to blunt-nosed leopard lizard populations. Construction of facilities related to oil and natural gas production, such as well pads, wells, storage tanks, sumps, pipelines, and their associated service roads degrade habitat and cause direct mortality to leopard lizards, as do leakage of oil from pumps and transport pipes, and storage facilities, surface mining, and off-highway vehicle traffic (Mullen 1981, USFWS 1985a, Kato and OFarrell 1986, Madrone Associates 1979, Chesemore 1980). Dumping of waste oil and highly saline wastewater into natural drainage systems also degrades habitat and causes direct mortality, but these activities are no longer permitted. Lizards displaced by degraded or lost habitat may be unable to survive in adjacent habitat if it is already occupied or unsuitable for colonization (USFWS 1985a, Williams and Tordoff 1988). Direct mortality occurs when animals are killed or buried in their burrows during construction, killed by vehicle traffic on access roads, drowned or mired in pools of oil (Montanucci 1965, Mullen 1981, Kato and OFarrell 1986, Kato et al. 1987b) and uncovered oil cellars (USFWS 1988), or fall into excavated areas from which they are unable to escape (OFarrell and Sauls 1987).

Although lizards occur in areas of light petroleum development and recolonize oil fields that have been abandoned (OFarrell and Kato 1980, Chesemore 1980, OFarrell 1980, Williams in litt. 1989), their population densities decrease as oil activity increases (Jones 1980, OFarrell and Kato 1980, Mullen 1981, Kato and OFarrell 1986, OFarrell and Sauls 1987). Eighty-three percent of the blunt-nosed leopard lizard population on Elk Hills Naval Petroleum Reserves in California inhabited areas where little or no petroleum-related activity had occurred (Kato and OFarrell 1986). D.J. Germano (pers. comm.) reports relatively high numbers of blunt-nosed leopard lizards at the Kern Front Oil Fields despite the high level of oil activity.

Livestock grazing can result in removal of herbaceous vegetation and shrub cover, destruction of rodent burrows used by lizards for shelter, and associated soil erosion if the stocking rate is too high or animals are left on the range too long after annual plants have died (Chesemore 1981, Williams and Tordoff 1988). Unlike cultivation of row crops, which precludes use by leopard lizards, light or moderate grazing may be beneficial (USFWS 1985a, Germano and Williams 1993, Chesemore 1980). Chesemore (1980) suggested that 15 percent to 30 percent ground cover was optimal for leopard lizard habitat and greater than 50 percent was unsuitable. Researchers have hypothesized that leopard lizards prefer lightly grazed grasslands since these are dominated by Arabian grass, a low, sparsely growing, introduced annual grass, whereas ungrazed areas are dominated by red brome which is a taller, denser inroduced grass (Mullen 1981, Chesemore 1980). However, domination by Arabian grass may be partly or predominately due to precipitation, soil structure, and other environmental variables instead of grazing intensity, based on long-term studies at several sites within the geographic range of the blunt-nosed leopard lizard (Williams et. al 1993b, Germano and Williams 1994b, Williams and Nelson in press, Williams and Germano 1991). On the Elkhorn Plain Ecological Reserve, high percentages of ground cover (nearly 100 percent in 1991-1993, 1995) may not have provided optimum habitat conditions, but grasshoppers and large moths and other prey for leopard lizards were abundant under these conditions. Blunt-nosed leopard lizards survived such conditions in similar proportions in grazed and nongrazed areas both in years of low and high plant productivity, though drought and lack of grazing during several years of the study makes results inconclusive (Williams et al. 1993b, Germano et al. 1994, Germano and Williams 1994b, Williams and Nelson in press, D.F. Williams unpubl. data).

The use of pesticides may directly and indirectly affect blunt-nosed leopard lizards (Germano and Williams 1993, Jones and Stokes 1977, California Department of Food and Agriculture 1984, Williams and Tordoff 1988). The insecticide malathion has been used since 1969 to control the beet leafhopper (California Department of Food and Agriculture 1984). California Department of Food and Agriculture treats areas on the west side of the San Joaquin Valley, from Merced to San Luis Obispo Counties, up to three times a year, depending on the seasonal densities of the sugar beet leafhopper and whether or not it is carrying the curly-top virus (H.L. Foote pers. comm.). Pretreatment surveys for blunt-nosed leopard lizards are conducted so that inhabited areas can be avoided, if possible.

Although the acute and chronic effects of malathion toxicity to leopard lizards are unknown (R.A. Marovich pers. comm.), Hall and Clark (1982) found that acute oral administration of malathion was relatively non-toxic to another lizard of the family Iguanidae. The most important effects of malathion on the blunt-nosed leopard lizard may be those associated with the reduction of insect prey populations (California Department of Food and Agriculture 1984). Because it degrades in approximately 48 hours, the direct effect of this insecticide on the abundance of prey species is thought to last for 2 to 5 days (California Department of Food and Agriculture 1984). Aerial application of malathion may reduce the availability of food for reproducing lizards in the spring, and later for hatchlings when they should be storing fat to sustain themselves during their first winter (Kato and OFarrell 1986). During recent consultation with the Service, the California Department of Food and Agricultures curly top virus control program was modified to increase protection measures, including increasing the use of biocontrol and integrated pest management techniques in blunt-nosed leopard lizard habitat (USFWS in litt. 1997a).

Blunt-nosed leopard lizard mortality is known to occur as a result of regular automobile traffic and off-road vehicle use (Tollestrup 1979b, Uptain et al. 1985, Williams and Tordoff 1988). Little information is available regarding the relative effect of this cause of mortality, but habitat fragmentation has accompanied the construction of roads. Typically roads surround and often bisect remaining fragments of habitat, increasing the risks of mortality by vehicles and strengthening the population effects of isolation.

5. Conservation Efforts

The blunt-nosed leopard lizard was listed as endangered by the U.S. Department of the Interior in 1967 (USFWS 1967) and by the State of California in 1971 (Table 1). A recovery plan was first prepared in 1980 (USFWS 1980a) and revised in 1985 (USFWS 1985a). Conservation efforts have included habitat and population surveys, studies of population demography and habitat management, land acquisition, and development of management plans for public lans that have benefitted blunt-nosed leopard lizards as well as other listed species (see the Introduction, 3. Conservation Efforts at the Community Level and Table 2).

Large-scale habitat surveys include those for the California Energy Commissions Southern San Joaquin Valley Habitat Preservation Program (Anderson et al. 1991), the Carrizo Plain Natural Area (Kakiba-Russell et al. 1991), Elk Hills Naval Petroleum Reserves in California (OFarrell and Matthews 1987, OFarrell and Sauls 1987, EG&G Energy Measurements 1995a,b), USBLM lands in Fresno, San Benito, and Monterey Counties (OFarrell et al. 1981), and a survey of 12,000 hectares (30,000 acres) of natural land in western Madera County (Williams 1990). There also have been numerous smaller-scale preproject surveys as part of the Sec. 7 and 10(a) permit processes of the Endangered Species Act, and National Environmental Policy Act and California Environmental Quality Act laws and regulations. Most of these have taken place in the southern San Joaquin Valley in Kern and western Kings Counties.

The CDFG conducted aerial surveys between 1976 and 1985 to determine the extent of remaining natural lands in the San Joaquin Valley (USFWS 1980a, 1985a). Survey maps were compared with baseline maps hand drawn from EROS 45.7 by 45.7-centimeter color infrared high altitude photos, taken in August 1974. The loss of undeveloped land in each of 20 Essential Habitat areas was compared for the years 1983 and 1985, the years most recent surveys were conducted.

In 1985, USFWS (USFWS in litt. 1985) proposed that 3,345 hectares (8,265 acres) in the Firebaugh, Whitesbridge, and Pixley Refuge Essential Habitat areas be acquired using Land and Water Conservation Fund Act funds. However, because of funding constraints, this plan has not been implemented.

Studies of population ecology and habitat management of leopard lizards have been conducted by several researchers funded by the USBLM, U.S. Department of Energy, Bureau of Reclamation, Service, and CDFG. The results of two research investigations of blunt-nosed leopard lizard food habits and home range size have been published since 1985 (Kato et al. 1987b, 1987b). Studies of demography and habitat management on the Elkhorn Plain have been on-going since 1987 (Williams et al. 1993b, Germano and Williams 1994b, Germano et al. 1994, Endangered Species Recovery Program unpubl. data). Similarly, since 1985, studies of demography have been ongoing at Pixley National Wildlife Refuge (Uptain et al. 1992, Williams and Germano 1991, Endangered Species Recovery Program unpubl. data). Other studies of habitat management and restoration have taken place at the Kern Fan Element by the California Department of Water Resources (J. Shelton and S. Juarez pers. comm.).

Though population viability analyses are an important aspect of conservation planning for this species, recent single-population analyses (Buechner 1989, Endangered Species Recovery Program studies in progress) are inadequate for two main reasons: (1) there are insufficient data on demographics of blunt-nosed leopard lizards from several sites representing the range of environmental conditions to which the species is exposed; and (2) the data are not representative of the temporal variation of the environment. Before modeling can become a useful tool for conservation planning, data needed to conduct metapopulation modeling must be gathered. These data include demographics of individual populations, the carrying capacity of the habitat of each, and their connectivity (rate of movement). Despite the shortcomings of current information, recent studies have shown that blunt-nosed leopard lizards can withstand severe, long term drought by remaining dormant for up to 22 months, and have the reproductive capacity for irruptive population growth when conditions are favorable (Williams et al. 1993b, Germano et al. 1994, Germano and Williams 1994b).

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency County bulletins governing use of rodenticides have greatly reduced the risk of significant mortality to blunt-nosed leopard lizard populations by State and county rodent-control actvities. The California Environmental Protection Agency, California Department of Food and Agriculture, county agricultural departments, CDFG, and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency collaborated with the Service in the development of County Bulletins that both are efficacious and acceptable to land owners (R.A. Marovich pers. comm.).

6. Recovery Strategy

The more important questions that must be addressed before or simultaneous with purchase of land or conservation easements, is how to preserve and enhance populations on existing habitat. Substantial habitat is in public ownership or a conservation program, but appropriate habitat management prescriptions for these parcels mostly are unknown. No parcel currently is being specifically managed to optimize habitat conditions for this species. Thus, the three most important factors in recovering the blunt-nosed leopard lizard are:

- determining appropriate habitat management and compatible land uses for blunt-nosed leopard lizards;

- protecting additional habitat for them in key portions of their range; and

- gathering additional data on population responses to environmental variation at representative sites in their extant geographic range.

A population monitoring program and a range-wide population survey are needed to determine current population sizes and habitat conditions, track lizards responses to environmental variation and changing land uses, and rank areas and parcels for protection by purchase of title or easement. Special attention must be directed to surveys in potential habitat in central Merced County, where ground surveys have not been conducted.

Also needed is an analysis of extinction patterns on different-sized, isolated blocks of natural land on the Valley floor to gain insight into the effects of habitat size and diversity on population viability. Because several important populations are isolated on fragmented natural land on the Valley floor and along its southern and western perimeter, ultimately, determining viable population size, genetic variation, and methods to enhance population movements and restore habitat on retired farmlands are needed to ensure recovery.

Recovery Actions.-- Principal recovery actions for the blunt-nosed leopard lizard should focus on information needed to make informed decisions about land acquisition and habitat management and restoration, and measure progress toward recovery. Habitat protection is important, and in some portions of the geographic range of blunt-nosed leopard lizards, it has a high priority. Yet, while habitat protection goals may require many years to achieve, and some may never be reached, other actions must be implemented. Needed actions are:

- Determine appropriate habitat management and compatible land uses for blunt-nosed leopard lizards.

- Conduct range-wide surveys of known and potential habitat for presence and abundance of blunt-nosed leopard lizards.

-

Protect additional habitat for them in key portions of their range; areas of

highest priority to target for protection are:

- Natural lands in western Madera County;

- Natural lands in the Panoche Valley area of Silver Creek Ranch, San Benito County;

- Agricultural and natural land between the north end of the Kettleman Hills and the Guijarral Hills and the Guijarral Hills and Anticline Ridge (western rim of Pleasant Valley, Fresno County) to restore and protect a corridor of continuous habitat for blunt-nosed leopard lizards and other species without the ability to move through irrigated farmland;

- Natural lands west of Highway 33 and east of the coastal ranges between the Pleasant Valley, Fresno County, on the north and McKittrick Valley, Kern County, on the south;

- Natural lands of the linear, piedmont remnants of their habitat west of Interstate Highway 5 between Pleasant Valley and Panoche Creek, Fresno County;

- Natural lands in upper Cuyama Valley.

- Gather additional data on population responses to environmental variation at representative sites in its extant geographic range.

- Design and implement a range-wide population monitoring program.

-

Protect additional habitat for blunt-nosed leopard lizards in the following

areas (all are of equal priority):

- Natural and retired agricultural lands around Pixley National Wildlife Refuge, Tulare County, with an objective of expanding and connecting the Refuge units with each other and with the Allensworth Ecological Reserve;

- Natural land in and around the Elk Hills Naval Petroleum Reserves in California and Lokern Natural Area with the objective of expanding and connecting existing lands with conservation programs;

- Natural and retired agricultural lands in the Semitropic Ridge Natural Area, Kern County, with the objective of expanding and connecting existing reserves and refuges.